A deep dive comparison between The 12-Week Year and OKRs as complete execution systems.

Created: 09th Feb., 2026 • by Dan Mintz

Get the 12-Week Year template used by our team

Written by Dan Mintz, a leading productivity strategist, expert in The 12-week year, and the founder of the 12-Week Breakthrough Program. Wharton MBA, MIT Data Scientist, 3x Entrepreneur. Worked with dozens of professionals to transform their lives in 12 weeks, achieve 10x productivity, and overcome inconsistency, overwhelm, and procrastination.

You’re drowning in projects. You set goals every quarter, maybe even weekly. But when you look back, you’re busy – not productive. You’re working hard but not hitting what actually matters.

I’ve spent years implementing productivity systems with dozens of clients, and I keep seeing the same pattern: ambitious professionals adopt either OKRs or the 12-Week Year, execute for 4-6 weeks, then quietly abandon the system when it doesn’t “stick.”

The problem isn’t the systems. It’s choosing the wrong one for your situation.

This guide is for you if you’re:

This guide is NOT for you if you’re:

After implementing both systems extensively – the 12-Week Year with solo consultants and OKRs with small product teams – I can tell you definitively: they solve different problems. Understanding which problem you actually have will determine which system works.

This article is part of our larger article series comparing The 12-Week Year to other productivity systems,

Before we compare, let’s be precise about what we’re evaluating.

Created by Brian Moran, the 12-Week Year isn’t just “quarterly goals.” It’s a complete framework covering:

Vision Architecture: You start with a 3-year vision grounded in personal identity and meaning, cascade to 1-year measurable outcomes, then translate to 12-week execution goals. This multi-horizon structure prevents you from losing the forest for the trees.

Goal Selection via 80/20: The system forces brutal prioritization. You can’t have 12 goals. You pick 1-3 critical outcomes that will drive disproportionate results. Everything else is deliberately ignored.

Lead Action Tracking: Here’s the distinctive feature—you don’t just measure outcomes (lag indicators). You track the specific weekly actions (Most Important Tasks) that cause those outcomes. Your scorecard shows execution percentage: “Did I complete my committed MITs this week?”

Calendar as Control System: The 12-Week Year is prescriptive about execution. MITs must be scheduled in time blocks. If it’s not on your calendar, it doesn’t exist. This forces confrontation with reality—you can’t commit to more than your calendar allows.

Weekly Planning Ritual: Every week, you conduct a structured planning session reviewing last week’s scorecard, planning this week’s MITs, identifying risks. This creates tight feedback loops.

In my experience implementing this with 30+ clients, the system works because it solves the fundamental problem most knowledge workers face: the gap between knowing what to do and actually doing it. It’s brutally tactical.

Created by Andy Grove at Intel, popularized by John Doerr at Google, OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) are fundamentally different.

Objectives + Key Results Structure: An Objective is inspirational direction (“become the fastest browser in the world”). Key Results are measurable outcomes (“achieve 10x faster JavaScript execution than IE7”). This pairing creates clarity—vision plus measurement.

Radical Transparency: Every employee’s OKRs are public. You can see what the CEO is working on, what the engineering team prioritizes, what your peer is focused on. This visibility enables coordination without bureaucracy—if you need to know if Android team is prioritizing email integration, you look up their OKRs. No meeting required.

Committed vs Aspirational Goals: This is critical. Some OKRs are committed (you must hit 1.0, like regulatory compliance). Others are aspirational stretch goals (0.6-0.7 is excellent). The system requires explicitly labeling which is which.

Cascading Alignment: Company OKRs inform team OKRs, team OKRs inform individual OKRs. But it’s not pure top-down—there’s negotiation. Teams propose OKRs that support company goals, but they have agency in how.

Quarterly Cadence with Scoring: You score each Key Result 0.0-1.0 at quarter-end. This creates data on execution quality and surfaces patterns (if you consistently score 1.0, you’re sandbagging; if you score 0.3, goals are unrealistic or you have execution problems).

Having implemented OKRs with three different product teams (ranging from 8-25 people), the system works because it solves coordination failure. When teams work in silos, you get duplicated effort, conflicting priorities, and nobody knows what others are building. OKRs make dependencies explicit.

Get the 12-Week Year template used by our team

12-Week Year: The system provides explicit scaffolding for vision work. You start by writing your 3-year vision grounded in personal values and identity—not just career goals. Then you cascade: what 1-year outcome would be a major milestone toward that 3-year vision? Then: what 12-week goal represents meaningful progress toward that 1-year outcome?

This multi-horizon architecture prevents short-term tunnel vision. When I’m 6 weeks into a 12-week cycle and feeling the grind, I revisit my 3-year vision to remember why this matters. The system forces that connection.

Example from my practice: A client wanted to “grow revenue” (vague). Through 12-Week Year vision work, we uncovered his real 3-year vision: “build a business that funds a lifestyle of 6 months working, 6 months traveling with family.” That clarity changed everything—his 1-year goal became “achieve $200K revenue with systems that don’t require my daily presence,” and his 12-week goal was “systematize client onboarding and delivery.” Totally different than “grow revenue 20%.”

OKRs: The system assumes you’ve already done strategy work elsewhere. OKRs don’t help you figure out what markets to pursue or what products to build. They’re the execution layer that translates existing strategy into measurable quarterly goals.

Google, Intel, Adobe—these companies had clear strategies before implementing OKRs. The OKR system made strategy legible and executable across the organization.

In practice, teams often set OKRs without sufficient strategic clarity, which leads to thrashing. You hit your OKRs but later realize they were the wrong goals. The system doesn’t prevent this.

Winner for vision integration: 12-Week Year. It explicitly scaffolds the vision → annual → quarterly → weekly cascade. OKRs assume you’ve done that work elsewhere.

12-Week Year: The system is dogmatic: 1-3 goals maximum for a 12-week cycle. More than that and you’re diluting focus. The book literally says “you can have any number of priorities as long as they fit inside a short list.”

This forced constraint is uncomfortable but powerful. When a client insists they need 5 goals, I ask: “Which 2 should we delete?” They usually can’t decide, which proves they don’t actually believe all 5 are critical. The 80/20 principle is baked into the system.

The prioritization happens through two questions:

That second question is brutal. When you try to schedule 5 goals worth of MITs into your actual calendar, you discover there aren’t enough hours. Reality forces prioritization.

OKRs: The recommendation is 3-5 OKRs, but the system doesn’t enforce this. I’ve seen teams with 8-10 OKRs per quarter, which defeats the purpose. Without someone playing gatekeeper (usually a manager or CEO), OKR lists become Christmas trees—decorated with so many objectives you can’t see what matters.

The better OKR implementations I’ve worked with use the “must fit on one page” rule. If you can’t fit all your OKRs on one page with readable font, you have too many.

Prioritization happens through dependency mapping. When teams make their OKRs public, conflicts surface: “Wait, my OKR requires engineering to complete X, but engineering’s OKR deprioritizes X.” These negotiations force trade-offs.

Winner for forced prioritization: 12-Week Year. The 1-3 goal maximum is non-negotiable. OKRs rely on discipline that many teams lack.

12-Week Year: The quarterly cycle creates urgency that annual planning destroys. With a 12-month timeline, you procrastinate for 9 months. With 12 weeks, you feel the deadline from week 1.

But the real power is the weekly rhythm. Every week includes:

This creates a tight feedback loop. If you’re off track in week 4, you discover it immediately and adjust—not at week 12 when it’s too late.

The system treats the week as the “natural behavioral planning unit”—short enough for feedback, long enough for meaningful work.

From my practice: I run my consulting business on 12-week cycles. Every Monday 8-9am is sacred—Weekly Planning Session, non-negotiable. Every Friday 4:30-5pm is Weekly Review. This ritual has produced more consistent execution than any motivation technique I’ve tried. The rhythm becomes automatic.

OKRs: Quarterly cycles are standard, but the weekly rhythm is less prescriptive. Best practices suggest weekly or bi-weekly check-ins (15-30 minutes) where you:

But many teams do monthly check-ins or no check-ins until quarter-end. Without discipline, OKRs become “set in week 1, score in week 13, no course correction in between.”

The better implementations use traffic light systems (green/yellow/red status) visible on dashboards. This creates pressure—nobody wants red OKRs visible to the whole company.

Winner for execution rhythm: 12-Week Year. The weekly planning and review sessions are mandatory and structured. OKRs suggest weekly check-ins but don’t enforce them.

This is where the systems diverge most fundamentally.

12-Week Year: Lead Actions + Lag Outcomes

The brilliance of the 12-Week Year is dual-track measurement:

Lag indicators (outcomes): Did you hit your 12-week goal? This is binary—either you launched the product or you didn’t, either you hit $50K revenue or you didn’t.

Lead indicators (actions you control): Did you complete your weekly MITs? This is measured as execution percentage.

Example from my business:

The insight: I control whether I make 5 calls. I don’t fully control whether prospects sign. By tracking lead actions, I focus on what I can control. If I execute at 80%+ for 12 weeks and still don’t hit my lag goal, I learn something—either my actions don’t drive the outcome (bad strategy) or the goal was unrealistic (bad estimation).

This is profoundly different from only measuring outcomes. Outcome-only measurement is demoralizing when external factors intervene. Lead action tracking creates agency.

OKRs: Outcome-Focused Key Results

OKRs measure outcomes, full stop. Key Results are lag indicators:

There’s no prescribed system for tracking the activities that drive those outcomes. Some teams add “inputs” to their tracking (number of experiments run, number of features shipped), but this isn’t part of the core OKR framework.

The scoring is 0.0-1.0:

This creates interesting dynamics. When a team scores 0.4 on an aspirational OKR, the question isn’t “did we fail?” It’s “was the goal unrealistic, or did we have execution problems?” You need qualitative judgment, not just the number.

From my work with product teams: We implemented OKRs for an 8-person team building a SaaS product. Their Q2 OKR was “Achieve 1,000 paid users (from current 200).” They scored 0.5—hit 600 users.

Post-mortem revealed: they shipped the features on time (execution was solid), but conversion rate was lower than projected (their assumption was wrong). The OKR score of 0.5 didn’t tell them why they missed. We had to add qualitative analysis.

Contrast this with 12-Week Year: if their lead action was “ship 3 features + run 5 conversion experiments,” they could score execution (did we do the MITs?) separately from outcomes (did it work?). This creates clearer learning.

Winner for measurement clarity: 12-Week Year. The lead/lag distinction creates better feedback. OKRs conflate execution quality with outcome quality.

12-Week Year: Prescriptive Execution Discipline

The system doesn’t just tell you to “achieve your goals.” It tells you exactly how:

Step 1: Break goals into lead actions. For each 12-week goal, identify 3-5 actions you control that drive that outcome. Example: Goal is “launch MVP product.” Lead actions might be “complete user interviews,” “build core feature set,” “conduct beta testing.”

Step 2: Convert lead actions to weekly MITs. Each week, you schedule 2-3 MITs that advance your lead actions. These are time-boxed: “Tuesday 9am-12pm: Complete user interview synthesis and identify top 3 feature priorities.”

Step 3: Schedule MITs in calendar blocks. This is non-negotiable. The system says “a task not scheduled in your calendar is a wish, not a plan.” When you try to fit MITs into your actual calendar (around meetings, commitments, life), you confront reality. Often you realize you can’t execute 3 goals—you can only execute 1.

Step 4: Execute in deep work blocks. The system integrates Cal Newport-style deep work principles. MIT execution should happen in distraction-free blocks. If an MIT requires 3 hours of focused work, you schedule a 3-hour block, eliminate interruptions, and execute.

Step 5: Track execution weekly. Your scorecard shows: “Committed to 8 MITs this week. Completed 7. Execution rate: 88%.”

This level of prescription is what makes the system work for people with execution problems. It’s not motivational fluff—it’s systematic behavioral engineering.

Example from my consulting: A client (marketing consultant) had a goal to “write a book in 12 weeks.” We broke this into lead actions:

Weekly MITs:

She scheduled these in her calendar with phone on airplane mode. For 12 weeks, she executed at 85% average (missed some weeks due to client emergencies). At week 13, she had a complete 25,000-word manuscript. The prescriptive mechanics made it real.

OKRs: Flexible Framework, Minimal Execution Guidance

OKRs tell you what to achieve (Key Results) but not how to execute. The assumption: you’re a competent professional who knows how to manage your work. OKRs provide the target; you figure out the path.

This flexibility is a feature, not a bug. Different teams need different execution approaches. An engineering team might use sprints. A sales team might use pipeline management. OKRs don’t prescribe the mechanics.

What OKRs do prescribe:

But there’s no “schedule your work in calendar blocks” equivalent. No “track lead actions” mandate. The system is more like principles than process.

From my product team work: We implemented OKRs with a 12-person engineering team. Their Q3 OKR was “Reduce API response time from 500ms to 200ms.” How they achieved it was up to them—they tried caching strategies, database optimizations, code refactoring. The OKR didn’t prescribe which approach. It just measured the outcome.

This worked because they were experienced engineers who knew how to solve performance problems. If they’d been junior or unfamiliar with the domain, the OKR wouldn’t have helped—they needed execution guidance, not just a target.

Winner for execution prescription: 12-Week Year. If you need someone to tell you exactly how to structure your work, 12WY does that. OKRs assume you already know.

12-Week Year: Personal Accountability Through Self-Confrontation

The accountability mechanism is internal. Your scorecard is primarily for you, not public performance review.

Every week, you face the truth: “Did I do what I said I’d do?” If your execution rate is 60%, you can’t hide from it. The data confronts you.

This works through:

The system doesn’t rely on external pressure. It’s about building internal integrity—do your actions match your commitments?

Can be adapted for team accountability: Some small teams run 12-week cycles together, sharing scorecards in weekly meetings. This adds peer accountability—nobody wants to consistently show 40% execution while teammates hit 85%. But the system works solo.

OKRs: Organizational Accountability Through Transparency

The accountability is social and structural. Your OKRs are public. Your manager sees them. Your peers see them. If you commit to “launch 5 features” and only ship 2, everyone knows.

This creates healthy pressure:

The danger: this can become performative. Teams report “green” status to save face, then reveal “red” reality at quarter-end. Psychological safety is critical—people must feel safe admitting “I’m behind.”

At Google, execs model vulnerability: “I’m at 0.4 on my OKR, here’s why, here’s my plan to recover.” This signals that honesty is valued over fake success.

Winner depends on context:

12-Week Year: Failure as Execution Data

When you miss goals in the 12-Week Year, the system forces diagnosis through execution data.

Example: My Q4 goal was “sign 3 new clients.” I only signed 1 (33% of goal). Was this failure?

I check my scorecard:

So execution was solid (88% overall). I did the MITs I committed to. This tells me: the actions didn’t drive the outcome. Either my strategy was wrong (those aren’t the right MITs to sign clients) or the goal was unrealistic (signing 3 clients in 12 weeks is harder than I estimated).

If my execution rate had been 40%, different conclusion: I had the right strategy but didn’t execute. Need more discipline.

This distinction is critical for learning. The scorecard disambiguates execution problems from strategy problems.

Course correction happens weekly: If you’re at week 6 with 45% execution rate, you don’t wait until week 12. You adjust immediately—reduce MITs, change tactics, or admit the goal is unrealistic.

OKRs: Failure as Aspiration (Sometimes)

This is where OKRs get nuanced. There are different kinds of “failure”:

Committed OKR failure: You committed to hit regulatory compliance deadline and scored 0.6. This is actual failure—consequences follow.

Aspirational OKR “failure”: You set a moonshot goal (10x improvement) and scored 0.7 (achieved 7x improvement). This is success—you accomplished more than you would have with a conservative goal.

The system requires labeling goals upfront: is this committed or aspirational? That determines how to interpret the score.

Google’s culture: consistently hitting 1.0 on aspirational OKRs means you’re sandbagging. They want you scoring 0.6-0.7, proving you’re stretching.

But without strong culture, this breaks down. Teams get punished for scoring 0.7, so they stop setting stretch goals. Leaders must explicitly celebrate “good failures” on ambitious OKRs.

Course correction: Happens in weekly/bi-weekly check-ins. If an OKR is red at week 4, options are:

The key: revisions must be documented and justified. You can’t silently sandbag.

Winner for learning from failure: 12-Week Year. The lead action scorecard creates clearer feedback about why you missed goals.

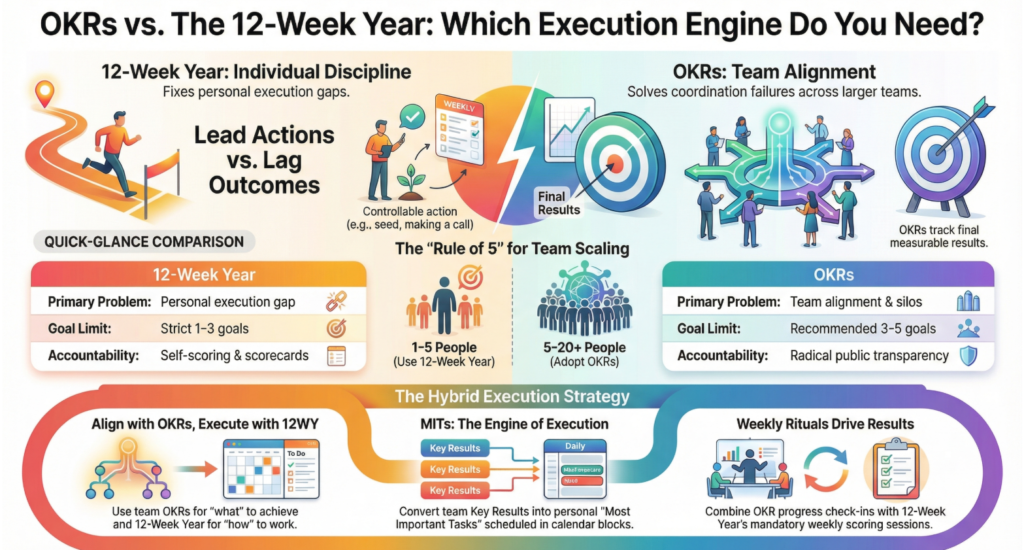

Here’s the insight I wish I’d had earlier: these systems solve different problems and can be complementary.

How to combine OKRs (team level) + 12-Week Year (individual level):

Use OKRs for alignment:

Use 12-Week Year for execution:

Example from a 10-person product team I worked with:

Team OKR (Q2):

Engineer’s 12-week goal (derived from team OKR):

Engineer’s MITs (lead actions):

Engineer’s scorecard:

This combination worked beautifully. The team OKR created alignment (everyone knew performance was the priority). Individual 12-week goals created ownership. MITs drove execution. Scorecard provided feedback.

The OKR solved “what should we work on together?” The 12-Week Year solved “how do I actually execute my part?”

| Dimension | 12-Week Year | OKRs |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Problem Solved | Planning-execution gap for individuals | Coordination and alignment for teams |

| Ideal Team Size | 1-5 people | 5-100+ people |

| Vision Integration | Explicit 3-year → 1-year → 12-week cascade | Assumes strategy done elsewhere |

| Goal Limit | Strict 1-3 goals per cycle | Recommended 3-5 OKRs (often broken) |

| Time Structure | Mandatory weekly planning + review | Suggested weekly check-ins |

| Measurement Focus | Lead actions (MITs) + lag outcomes | Lag outcomes (Key Results) only |

| Execution Prescription | Highly tactical (calendar blocking, deep work) | Principles-based (you decide how) |

| Accountability Mechanism | Self-confrontation through scorecard | Social transparency |

| Scoring System | Execution % (did I do my MITs?) | 0.0-1.0 outcome achievement |

| Transparency Requirement | Optional (can be private) | Mandatory (public OKRs) |

| Learning Curve | Medium (clear system, follow the book) | Medium-High (requires cultural buy-in) |

| When It Fails | Unrealistic MITs or lack of discipline | Too many OKRs, no psychological safety, or sandbagging |

| Best For | Solopreneurs, consultants, creators, executives managing themselves | Product teams, cross-functional projects, scaling organizations |

| Can Work Solo? | Yes, designed for it | No, needs team coordination to show value |

Client: Marketing Consultant (Solo)

Client: Software Engineering Manager (Team of 4)

Client: 15-Person Startup (Product + Eng + Sales)

Client: Executive at Large Corp

Client: 8-Person Agency

You’re solo or running a very small team (1-5 people). The system doesn’t require coordination infrastructure. You can implement it tomorrow alone.

Your biggest problem is execution discipline. You know what to do but don’t do it. You set goals but don’t follow through. You need structure that forces action.

You want prescriptive guidance. You don’t want to figure out “how to execute”—you want someone to tell you exactly what to do. Schedule MITs, track execution, review weekly. The system is a recipe.

You control your calendar. You have agency over how you spend your time. If your boss or clients dictate your schedule, 12-Week Year won’t help—you can’t commit to MITs you can’t protect.

You value lead action tracking. You want to measure what you control (actions), not just what you hope for (outcomes). This creates agency and clearer learning.

You’re coordinating a team of 5+ people. Multiple people need to work toward shared goals without stepping on each other. Transparency prevents siloed work.

Your biggest problem is alignment. Teams are working hard but on the wrong things. You need everyone pointing in the same direction.

You have (or can build) psychological safety. People must feel safe saying “I’m behind, I need help” without fear of punishment. If you punish failure, OKRs will fail.

You want outcome focus over activity tracking. You care about results, not checking boxes. Different team members might reach the same Key Result through different actions—OKRs allow that flexibility.

You’re willing to invest in cultural change. OKRs aren’t just a system—they’re a cultural intervention. They require transparency, continuous feedback, and comfort with public goal-setting.

You’re 5-15 people—small enough that coordination isn’t overwhelming, large enough that alignment matters.

You have both coordination and execution challenges. Teams need to align (OKRs solve this) and individuals need execution discipline (12-Week Year solves this).

You’re willing to maintain two parallel systems. OKRs at team level, 12-Week Year at individual level. This is more complex but powerful.

Both the 12-Week Year and OKRs make a dangerous assumption: you’ve chosen the right goals.

If you’re solving the wrong problem, executing flawlessly doesn’t matter. You can hit 95% execution on your MITs and sign zero clients because you targeted the wrong market. You can score 1.0 on all your OKRs and still fail as a business because your strategy was flawed.

These are execution systems, not strategy systems. They help you do what you decided to do. They don’t help you decide what to do.

From my experience: I’ve seen both systems produce flawless execution on terrible goals. A consultant who executed perfectly on a 12-week goal to “grow email list by 10,000 subscribers” but never converted subscribers to clients. A startup that hit all their OKRs around user growth but built a product nobody would pay for.

The systems can’t fix bad strategy. They can only expose it faster.

If you’re uncertain whether you’re pursuing the right goals, don’t start with execution systems. Start with strategy work: customer research, market validation, business model testing. Then use these systems to execute what you’ve validated.

Q: Can I use the 12-Week Year if I work in a corporate job with annual review cycles?

Yes, but with caveats. You can run personal 12-week cycles independently of corporate timelines—many of my corporate clients do this successfully. However, if your calendar is dominated by organizational fire drills and you lack agency over your time, the system struggles. The 12-Week Year requires ability to commit to and protect MITs. If your boss can commandeer your calendar at will, you’ll hit 40-50% execution rates and feel frustrated. In that environment, focus on negotiating calendar control before implementing the system.

Q: Do OKRs work for a team of 3 people, or is that too small?

OKRs can work for 3 people, but question whether you need them. The primary value of OKRs is coordination through transparency—preventing siloed work when teams operate independently. With 3 people, you probably coordinate naturally through daily conversation. The overhead of formal OKRs (writing them, tracking them, reviewing them) might exceed the value. Exception: if your 3 people work remotely or asynchronously and coordination is genuinely challenging, OKRs can help. But most 3-person teams are better served by simpler systems.

Q: What happens if I miss my 12-week goals? Do I just repeat them next cycle?

No—that defeats the purpose. If you miss a goal, diagnose why through your scorecard data. If your execution rate was 80%+ but you missed the goal, your strategy was flawed (those MITs don’t drive that outcome) or the goal was unrealistic. Adjust for next cycle—different goal, different approach, or more realistic target. If your execution rate was 40-50%, you have a discipline problem, not a strategy problem. Don’t repeat the same goal with same MITs if you already proved that combination doesn’t work.

Q: How do you prevent OKRs from becoming just another to-do list?

This is a common failure mode. Prevention requires three things: First, limit to 3-5 OKRs maximum—if everything is a priority, nothing is. Second, ensure Key Results measure outcomes, not activities. “Ship 5 features” is a to-do item; “Increase user engagement 40%” is an outcome. Third, track progress weekly and publicly. If your OKRs sit in a document nobody looks at until quarter-end, they’re to-do items. Active weekly tracking keeps them alive.

Q: Can I combine elements from both systems? Like using OKR format but 12-Week Year execution mechanics?

Absolutely—this is what I recommend for many clients. Use OKR format for goal-setting (Objectives + measurable Key Results), but add 12-Week Year execution discipline (identify MITs for each KR, schedule them in calendar blocks, track execution weekly). This hybrid captures the clarity of OKRs with the execution rigor of 12-Week Year. Just don’t try to use both systems simultaneously in their pure forms—that’s too much overhead.

Q: Do these systems work for creative work that doesn’t have clear outcomes?

Yes, but requires adaptation. Creative work often has ambiguous outcomes (“write a compelling novel” is harder to measure than “acquire 100 customers”). For the 12-Week Year, focus lead actions on the creative process: “write 2,000 words/week” is measurable even if quality is subjective. For OKRs, define Key Results around tangible milestones: “complete first draft by week 12” or “receive feedback from 5 beta readers with 4/5+ rating.” The systems work when you translate creative goals into measurable progress indicators.

Q: How long does it take to see results with each system?

12-Week Year: You see execution data immediately (week 1 scorecard) but outcome results at week 13. Most clients report the first cycle feels clunky, second cycle feels better, third cycle becomes natural. Give it 2-3 cycles (24-36 weeks) before judging effectiveness.

OKRs: Team alignment improvements appear within 4-6 weeks (dependencies become visible, coordination improves). Outcome results appear at quarter-end. Cultural change takes 2-3 quarters—the first quarter people are skeptical, second quarter they’re tentatively bought in, third quarter it becomes “how we work.” Rush the cultural piece and OKRs become theater.

Q: What if my team wants to use OKRs but leadership isn’t bought in?

This usually fails. OKRs require top-down modeling—if executives don’t share their OKRs publicly and review them regularly, the system loses credibility. You can run OKRs within your team as a local experiment, but cross-team coordination (the main value) won’t happen without broader buy-in. Better approach: pilot OKRs with your team for one quarter, document the results (improved alignment, clearer priorities, faster problem-surfacing), then pitch the pilot results to leadership with a proposal to expand. Show, don’t tell.

Q: Is there a minimum time commitment for these systems to work?

12-Week Year: Budget 30-45 min weekly planning + 15-30 min weekly review = ~1 hour/week. Plus execution time for your MITs (that’s the actual work). If you can’t commit 1 hour/week to the system, it won’t stick.

OKRs: Individual time is lighter (15-30 min weekly check-ins), but team coordination time is heavier (weekly team OKR reviews, quarterly planning sessions). Budget 2-3 hours/quarter for OKR planning and 30-60 min/week for team check-ins. This scales with team size.

Q: What’s the biggest mistake people make with the 12-Week Year?

Setting unrealistic MITs. People commit to 15 MITs per week, execute 6, feel like failures, abandon the system. The scorecard is supposed to confront you with reality, not demoralize you. Start conservative: commit to 5-8 MITs per week that you’re 90% confident you can complete. Once you hit 80-90% execution for 3 consecutive weeks, you can add more. Building the habit of hitting commitments matters more than the volume of commitments.

Q: What’s the biggest mistake people make with OKRs?

Treating them as performance reviews. When you tie OKR scores directly to compensation or promotion decisions, people sandbag—they set goals they’re certain to hit because missing goals means smaller bonuses. This destroys the stretch goal philosophy. Better approach: use OKRs to evaluate team performance (did we achieve company objectives?) but evaluate individuals based on how they contributed to those objectives, not just whether they scored 1.0. Decouple individual performance reviews from OKR scores.