An extensive guide to finding the goals that matter most when you don’t know what to focus on

Created: 16 January, 2026 • by Dan Mintz

Get the 12-Week Year template used by our team

Written by Dan Mintz, a leading productivity strategist, expert in The 12-week year, and the founder of the 12-Week Breakthrough Program. Wharton MBA, MIT Data Scientist, 3x Entrepreneur. Worked with dozens of people to transform their lives in 12 weeks.

You’re likely using a fundamentally flawed process to choose your goals.

Wouldn’t you want a process that helps you choose the right goals?

Most people don’t even define goals – but that is another story and not in our scope. I assume you understand the importance of setting and executing on goals.

The small percentage who actually define their goals and attempt to execute on them use a fundamentally flawed process to choose the most optimal goals.

The ability to define and execute on the right goals is a key driver for your productivity and success.

I have worked with dozens of professionals on implementing the 12-Week Year as a productivity system, and I have experienced first hand how and why they choose the wrong goals, and why very few actually are able to zero in on the really vital few goals. Out of this experience, and 15 years of productivity research, I developed what I believe is the most optimal process to choose the right goals for you.

In this article you will learn the fundamentals of this process, the underlying philosophy, and practical ways to use it within the 12-Week Year system.

This article is part of our main goal pillar of achieving goals with the 12 week year.

Extraordinary results come from identifying the small set of high-leverage goals—the 10% of actions that drive 90% of your progress. Success is secured by enforcing the execution of these “vital few” through short operating cycles (12-Weeks), performance measurement, accountability, and rapid feedback loops.

This might remind you of the 80/20 law that is well known in the business world. And you are right. The 80/20 rule is a key productivity principle which is extremely well documented and validated. It is an empirical observation across economics, strategy, psychology, and performance science.

Here are several articles on this subject:

1. The 80/20 book – a classic.

2. The case for behavioral strategy – A McKinsey & Company study on the effects of few vital actions.

To select the best goal, the primary factor must be its potential impact on your overarching vision. While the SMART criteria provide necessary structure, they are not enough. The crucial step is to pinpoint the specific leverage a goal provides to effectively move you closer to your defined “standard of excellence.”

A goal should stretch your capabilities by at least 15% to be worth pursuing. If a goal is too simple, it loses its significance; however, stretching too far beyond 15% can become unachievable and damage motivation. The ideal goal finds the “sweet spot” that is challenging yet productive.

Personal productivity comes from identifying and repeatedly doing the small number of actions that create most results — and deliberately neglecting the rest.

In this way, we’re creating extreme focus and clarity on the most important areas that we must act upon in order to achieve optimized results.

When people choose goals, the process is often informal and intuitive:

As a result, they choose too many goals, across too many domains, with no clear sense of leverage.

This violates a basic principle of performance: A small number of goals create the vast majority of results. This principle — the Law of the Vital Few — is not a slogan. It is a guiding principle.

Yet most goal-setting approaches fail to operationalize it.

The 12-Week Year, as an integrated productivity system, does it very well.

Before explaining the solution, it is important to understand the failure modes.

People pursue 7–10 goals simultaneously. Attention fragments. Progress stalls.

Goals feel “important” but do not materially move the system forward.

Urgency, visibility, and social pressure distort judgment.

Annual goals lock people into bad choices for too long.

The result is not laziness — it is misallocation of resources such as time and effort.

The SMART methodology is a goal-setting framework designed to turn vague intentions into actionable, trackable plans. It is the industry standard for choosing goals, but you will soon see why it is not sufficient. Here are the components for the SMART system:

SMART goals improve clarity, and you should use them as part of your criteria for selecting goals. However, they do not improve the actual selection.

SMART goals can be high-impact — the framework does not prevent leverage. The problem is that SMART does not evaluate impact or leverage at all. It answers “Is this goal clear and executable?” It does not answer “Is this the most impactful thing to work on now?” Therefore, using SMART alone is insufficient for goal selection when the objective is meaningful progress toward a vision.

SMART is a goal-definition tool, not a goal-selection system.

The 12-Week Year treats SMART as a minimum standard, not a selection framework. Choosing a goal should follow at its core, the guiding principles described above in this article.

Get the 12-Week Year template used by our team

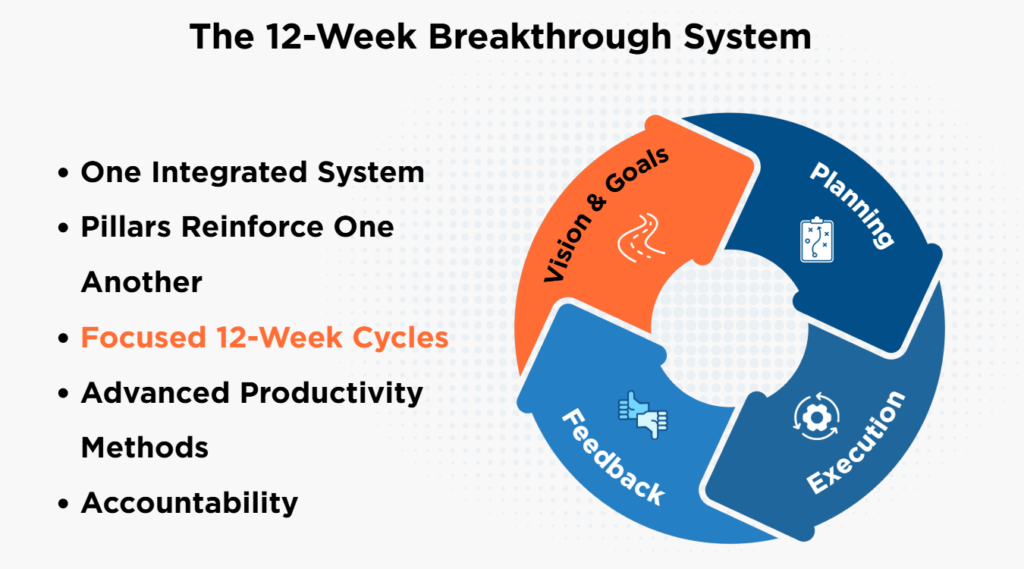

As I mentioned before, the 12-Week Year is an integrated system that has all the key components you need to run the most optimal productivity framework. Therefore, it is vital that you use this selection process as part of the 12-Week Year.

You might ask, “Can this selection process work on its own?” My answer would be yes; it would still be far superior than any other selection process out there. But to get a compounded result, it’s best to use it within an integrated productivity system such as the 12-Week Year.

I want to briefly describe the high-level logic of the process and its main components. A more detailed explanation of each and every step is below.

It is crucial that you understand the high-level logic of this selection process, what each step represents, and how to use it.

Remember:

The “Law of the Vital Few” is a fundamental guiding principle, as previously discussed in relation to goal selection. This core principle is the foundation for all the interconnected components, ensuring the system is engineered to produce outcomes that deliver the highest possible impact on your life.

The four elements or steps in this goal selection process are:

Vision is a crucial element of the 12-Week Year system. It begins with defining a three-year vision. This relatively long-term focus serves as an emotionally anchored, motivational North Star, providing the necessary drive to effectively implement the 12-Week Year.

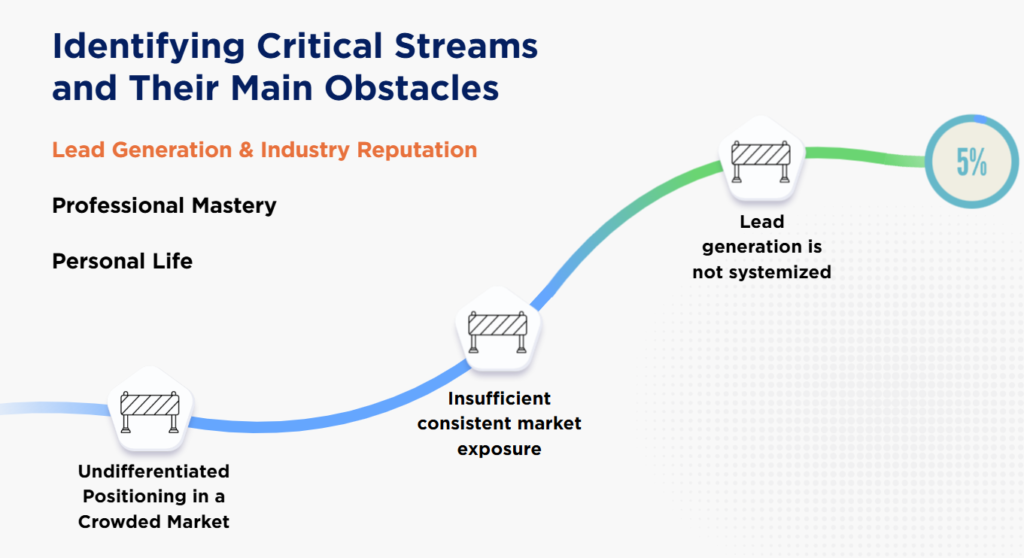

Following the definition of your vision, you must identify the three key streams or paths necessary to achieve it. Essentially, these streams represent the principal domains or areas in your personal or professional life that require change to bring your vision to reality.

For each of these streams or paths, you need to identify two or three main obstacles that prevent you from achieving your vision.

Once the streams and their corresponding obstacles are defined, you can identify and set goals. These goals should aim to remove or eliminate the obstacles, leading you toward the most optimal goals you can choose.

The logic underlying the use of vision, streams, and obstacles for reaching goals is based on both:

This rigorous process will yield the most realistic map of the playing field, clearly outlining the most highly leveraged areas, thereby providing you with optimal, high-impact results.

Here is the main spine of the goal selection process:

Let’s go over each of these steps.

Outcome:

Establish a clear future state (3-year vision) to serve as a directional reference point. The vision provides the necessary context to judge leverage and define constraints. Vision helps drive extreme clarity and focus.

A clear future state (3–5 years) that defines what “progress” means. A vision is a clearly chosen standard for who you are becoming and what winning looks like — vivid enough to feel real, flexible enough to survive change, and concrete enough to drive weekly execution. It is your anchor and emotional basis for staying motivated even on bad weeks.

Define the destination, not the journey. Why this step must exist (logic): Without a direction:

Here is our guide about vision in the 12-Week Year.

Group reality into no more than 2–3 major “streams” or paths required for the vision to become real. Streams are structural capability areas (e.g., Lead Generation, Personal Capacity, or Infrastructure) rather than task lists.

Restriction Rule: Streams restrict the search space so the “vital few” can be discovered. If a stream is not strictly required for the vision, it is excluded.

The few domains that must function for the vision to become real.

Identify no more than 2–3 streams that are necessary (not “important”).

Leverage cannot exist everywhere. Streams restrict the search space so the vital few can be discovered. Without streams:

One of the most misunderstood aspects of goal selection is where goals come from. In the 12-Week Year, goals

are not chosen randomly. They emerge from critical streams — core domains of performance. Examples:

The rule is simple and strict:

No more than three streams at a time.

Within each stream, the question is not “What should I improve?” It is:

“Where is progress currently constrained?”

This reframes goal selection from aspiration to diagnosis.

Identify the primary “big” obstacle within each stream (e.g., “Lack of Public Exposure”). Treat this as a container for further diagnosis, as big obstacles are usually effects rather than causes.

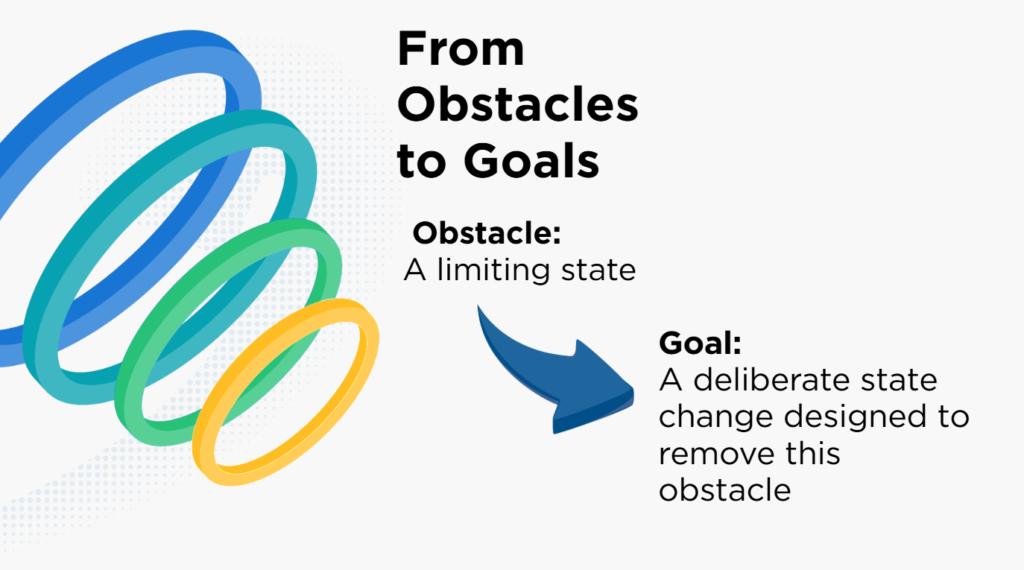

Obstacle = a limiting state.

So the relationship is:

Obstacle → Required State Change → Goal

Current-state constraints that limit progress even if effort increases. You can view obstacles on the path of your stream and look at them as what are the things that prevent you from achieving your vision and goals.

Describe obstacles as states, not actions.

Ask: What is structurally preventing movement here?

Evaluate each causal obstacle against four diagnostic tests to find the “first domino”:

Systems are governed by bottlenecks. Pushing non-constraints produces activity, not throughput. Without obstacle identification:

Obstacles uncover opportunities for extreme leverage or a way of applying the law of the vital few.

The foundation for obstacle principles is based on Systems Theory & Science.

3-4 goals that are an engineered response to an obstacle. The goal’s purpose is to weaken, remove, or bypass the obstacle.

Obstacle = a limiting state.

Goal = a deliberate state change designed to weaken or remove that limitation.

Design a goal that:

Once streams are defined, goal selection becomes precise. A high-leverage goal has three characteristics:

Importantly, this does not always result in a single goal. It results in a small set of vital goals — typically one to three.

This is the Law of the Vital Few applied structurally, not rhetorically.

Goals do not emerge naturally from obstacles. They are engineered responses. Without this step:

Effective goal selection starts with time alignment. The 12-Week Year uses a deliberate hierarchy:

Identity-based, directional, long-term, vivid, and emotionally resonant.

Concrete progress markers that make the vision actionable.

Short enough to create urgency, long enough to produce real change.

This hierarchy matters because goal selection is not isolated. It is the mechanism that connects future identity to present action.

Without milestones, the gap between vision and execution becomes too wide — and goal selection becomes guesswork.

A 3-year vision is too far to jump directly into 12-week goals. So you insert a 12-month layer as a realistic bridge — a milestone step towards your vision.

Flow becomes:

3-Year Vision → 12-Month Goals → 12-Week Cycles → Actions

This preserves logic, realism, and momentum instead of over-compressing the future.

The Outcome Rule: A valid goal is a state change achievable in 12 months. It is not a vanity metric or a simple task.

Even the best goal-selection process operates under uncertainty. There is no perfect foresight.

This is why the 12-week cycle matters. Short cycles enable:

Goals are treated as testable hypotheses:

“If we focus here, results should improve.”

If they do not, the system adapts — not after a year, but after weeks. This is where execution and goal selection reinforce each other.

Most systems separate:

The 12-Week Year integrates them. Goal selection is:

This integration is the real advantage.

Execution does not just achieve goals. It teaches you which goals matter. Over time, the system compounds judgment.

Most people do not fail because they cannot execute.

They fail because they are executing goals that should never have been chosen.

The 12-Week Year does more than improve productivity. It creates a forcing function for selecting the vital few goals that actually move the system forward.

That is why it works.

And why, over time, it produces not just better results — but better thinking.

The 12-Week Year is a productivity and execution system that compresses the traditional annual planning cycle into 12-week periods. Instead of setting goals for an entire year, you operate in focused 12-week cycles that function as your “year.”

This system was developed by Brian Moran and Michael Lennington and is built on a simple but powerful insight: annual goals create a false sense of time abundance. When you have 12 months to accomplish something, urgency doesn’t kick in until the final quarter. By then, you’ve lost momentum and clarity.

The 12-Week Year solves this by:

The system includes weekly planning, daily scorekeeping, and accountability mechanisms to ensure you execute on your goals, not just set them. It’s not just about working faster — it’s about working on the right things with relentless consistency.

The original 12-Week Year book provides an excellent execution framework but offers limited guidance on how to actually select which goals to pursue. It assumes you already know what your vital few goals are.

This goal selection process fills that gap by providing a rigorous, systematic method to identify the highest-leverage goals before you enter a 12-week cycle.

The key differences:

Original 12-Week Year approach:

This goal selection process:

Think of it this way: the original 12-Week Year is a high-performance engine. This goal selection process is the navigation system that ensures you’re driving in the right direction. Together, they create an integrated productivity system that both identifies the right goals and executes them relentlessly.

SMART goals are excellent for defining and structuring goals, but they are fundamentally insufficient for selecting which goals to pursue in the first place.

Here’s why:

SMART helps you answer: “Is this goal clear, measurable, and achievable?”

But it doesn’t answer: “Is this the most impactful thing I could work on right now?”

You can have a perfectly SMART goal that is:

…and still have it be the wrong goal because it doesn’t address your actual constraints or move you meaningfully toward your vision.

For example, “Increase social media followers by 1,000 in 12 weeks” is SMART. But if your real constraint is that you don’t have a productized offering to sell, growing your audience is working on the wrong problem. You’ll hit your goal and still make no progress toward your vision.

The SMART framework is a necessary minimum standard for goal formulation. But selecting goals requires a different lens: identifying where your system is actually constrained, where leverage exists, and which state changes will unlock the most progress.

Use SMART to define your goals once you’ve selected them. Use the Vision → Streams → Obstacles → Goals framework to select which goals are worth defining in the first place.

This is actually a diagnostic signal, not a problem.

If you can’t identify clear obstacles within a stream, it usually means one of three things:

1. The stream isn’t truly necessary for your vision

If you’re struggling to find meaningful obstacles, the stream might not be as critical as you thought. Ask yourself: “If I made zero progress in this stream for the next 12 months, would my vision still be achievable?” If the answer is yes, eliminate the stream and focus elsewhere.

2. You haven’t gone deep enough in your analysis

Obstacles often hide beneath surface-level descriptions. You might say “I need to improve my marketing” but that’s not an obstacle — it’s a vague category. The real obstacle might be “I have no systematic way to generate qualified leads” or “My messaging doesn’t clearly communicate value to my target audience.”

Use the diagnostic tests:

3. You’re already past the major constraints in this stream

Sometimes a stream has no major obstacles because you’ve already solved the critical bottlenecks. This is actually good news — it means you should shift focus to streams where obstacles do exist. Don’t create problems where none exist just to fill out your framework.

If you’re genuinely stuck, try working backward from your vision: “What has to be true for this vision to become real?” Then ask: “Is that true now?” The gap between those answers is your obstacle.

Use the four diagnostic tests described in the article. The right obstacle will pass multiple (ideally all) of these tests:

Unlock Test: If you removed this obstacle, what else would become easier automatically?

The right obstacle has cascading effects. Removing it doesn’t just solve one problem — it makes multiple other challenges easier or irrelevant. For example, if your obstacle is “No systematic lead generation process,” removing it makes sales easier, revenue more predictable, and hiring decisions clearer.

Dependency Test: Do other obstacles depend on this one?

The right obstacle is often structural — other problems exist because this one does. If you have obstacles A, B, and C, but B and C only exist because A exists, then A is your primary constraint.

Rate-Limiter Test: Is this currently capping progress regardless of effort?

The right obstacle is a bottleneck. You could work twice as hard, bring in more resources, or extend your timeline, and you’d still be stuck until this specific constraint is removed. If adding effort would solve it, it’s not your real obstacle.

Compounding Test: Does removing it create ongoing, long-term benefits?

The right obstacle, once removed, stays removed and continues delivering value. Solving “I don’t understand my customer’s core problem” has compounding benefits across all future marketing, sales, and product decisions. Solving “I need to send 50 emails this week” does not.

If your chosen obstacle passes 3-4 of these tests, you’ve likely identified a genuine constraint worth building a goal around. If it passes 0-1, keep digging — you’re probably looking at a symptom, not a cause.

Yes, but with strict constraints.

The framework allows for 2-3 streams maximum, and within those streams, you should have no more than 3-4 total goals across a 12-week cycle.

Here’s why this matters:

The mathematics of focus:

Working across multiple streams is realistic because different domains require different types of effort and often operate on different timescales. For example:

These don’t compete for the same resources or mental energy. You can make progress on both within a single week.

However, having multiple goals within the same stream is dangerous. If you’re trying to simultaneously build a lead generation system, launch a new productized service, and rebuild your website, you’re fragmenting effort within a single domain. Pick one — the one that removes the most critical constraint.

The rule: Multiple streams are acceptable if they represent genuinely separate domains of your life. Multiple goals within a single stream usually indicate you haven’t identified the real constraint yet.

This is a feature of the system, not a bug.

The 12-Week Year’s short cycles exist precisely because visions evolve as you gain information. You’re not locked into annual commitments — you get a checkpoint every 12 weeks.

During a cycle:

If your vision shifts mid-cycle, don’t abandon your current goals immediately. Finish the cycle — you’re already 4, 6, or 8 weeks in, and completing what you started builds discipline and provides valuable data. Use the remaining weeks to test whether the shift is real or just noise.

Between cycles:

This is when you reassess. At the end of each 12-week cycle, you have a natural checkpoint to ask:

If your vision has genuinely shifted, update it and run the goal selection process again: Vision → Streams → Obstacles → Goals. Your new cycle will reflect your updated direction.

The key principle:

A 3-year vision should be directionally stable but flexible in the details. If your vision is changing every 12 weeks, it’s not a vision — it’s a mood. But if it evolves gradually over multiple cycles as you learn more about yourself and your market, that’s healthy adaptation.

The 12-Week Year structure allows you to be both committed (within a cycle) and adaptive (between cycles). This balance is what makes the system resilient.

You don’t have more than 3 critical streams — you have 3 critical streams and several important-but-not-critical streams. The difficulty is distinguishing between them.

Here’s how to cut through the noise:

Apply the necessity test:

For each stream you’re considering, ask: “If I made zero progress in this stream for the next 12 months, would my 3-year vision become impossible to achieve?”

Most people discover that 1-2 streams are truly critical, and the rest are “nice to have” or “eventually necessary.”

Use time horizons:

Some streams are critical now, others become critical later. For example:

Focus on what’s critical for the current time horizon. The streams that matter most will shift as your situation evolves. That’s why you reassess every 12 weeks.

Identify dependencies:

Sometimes streams appear separate but one actually unlocks the other. For example:

Stream A might be the dependency — without energy, you can’t execute on revenue growth. In this case, health isn’t a separate parallel stream; it’s the foundational stream that enables the business stream.

The brutal truth:

If you’re trying to force 5+ streams into your framework, you’re avoiding hard choices. The Law of the Vital Few requires you to make trade-offs. Not everything can be a priority. The streams you exclude aren’t unimportant — they’re just not the highest leverage right now.

Choose 2-3. Execute relentlessly. Reassess in 12 weeks.

Your 3-year vision should be vivid and emotionally resonant, but not prescriptively detailed.

What to include:

What NOT to include:

The test of a good vision:

A vision that’s too vague (“be successful”) doesn’t constrain choices or create motivation. A vision that’s too detailed (“launch Product X to Market Y using Channel Z by Month 18”) becomes brittle and breaks when reality doesn’t cooperate.

Aim for the middle: clear enough to direct action, flexible enough to survive change.

Example of a well-calibrated vision:

“In 3 years, I run a consulting practice that generates $500K annually through high-value engagements with 10-15 clients per year. I’m recognized as a trusted advisor in my niche. I work 25 hours per week, primarily from home, and have the financial freedom and time to invest deeply in my family and health. My clients achieve measurable transformations, and I feel energized by the work rather than drained by it.”

This is vivid (you can see it), flexible (the exact clients and methods can evolve), and emotionally resonant (it describes a life worth working toward).

This is one of the most important distinctions in the framework, and it’s easy to conflate them.

12-month goals are strategic milestones that bridge your 3-year vision to executable action. They answer the question: “What state change needs to happen in the next year to keep me on track toward my vision?”

12-week goals are tactical execution targets nested within your 12-month goals. They represent concrete progress you can achieve in a single focused cycle.

The relationship:

Your 12-month goal defines the destination for the year.

Your 12-week goals are the stepping stones that get you there.

Example:

Notice: The 12-month goal is a state change (“establish a systematic process”). The 12-week goals are concrete outcomes that build toward that state change.

Why this matters:

Without 12-month goals, your 12-week goals become disconnected sprints with no strategic coherence. You might execute perfectly but still drift off course.

Without 12-week goals, your 12-month goals feel overwhelming and abstract. You know where you need to go but have no clear next step.

The hierarchy — 3-Year Vision → 12-Month Goals → 12-Week Goals → Weekly Actions — creates alignment from identity to daily execution. Each layer informs and constrains the one below it.

This is a common challenge because the most important goals are often qualitative state changes (“build a systematic process”) rather than simple metrics (“send 100 emails”).

Here’s how to make state-change goals measurable:

1. Define observable evidence of the new state

Instead of measuring the state itself, measure the evidence that the state exists.

2. Use binary milestones

Break the state change into yes/no checkpoints.

3. Track leading indicators

Measure the inputs that create the state, even if the state itself is emergent.

4. Use scorecard + narrative

Combine quantitative weekly scoring with qualitative assessment.

Each week, score yourself 0-100% on goal progress based on planned actions. Then add a brief narrative: “What changed this week? What evidence do I have that the state is shifting?”

Over 12 weeks, you’ll see both the trajectory (scores trending up) and the qualitative evidence (state actually changing).

The key principle:

State changes are real and important — don’t avoid them just because they’re harder to measure. Instead, get creative about defining what evidence would prove the state has changed, then measure that evidence.

A good rule: If you can’t identify any measurable evidence that a state change has occurred, you probably haven’t defined the goal clearly enough.

This is a high-quality problem, and it reveals important information about your goal-setting calibration.

First, celebrate it.

Finishing early means you executed well. That’s worth acknowledging.

Then, diagnose what happened:

Scenario 1: You underestimated your capacity

Your goals were achievable but not challenging enough. They didn’t stretch you to the 15% threshold described in the article.

Scenario 2: The obstacle wasn’t real

You thought something was a constraint, but it turned out to be easier to remove than expected. This means your obstacle identification needs refinement.

Scenario 3: You got lucky with external factors

Sometimes circumstances align in your favor — a client says yes faster than expected, a process works on the first try, etc.

What to do with the extra time:

Don’t add new goals mid-cycle. This fragments focus and undermines the discipline of the system.

Instead:

The 12-Week Year is a marathon of sprints. If you finish a sprint early, don’t immediately sprint harder — use the time to ensure you’re running in the right direction.

This framework works for any domain where you want to make meaningful progress toward a defined future state. The underlying logic — Vision → Streams → Obstacles → Goals — applies whether you’re building a business, improving your health, strengthening relationships, or developing a skill.

Professional/Business Example:

Personal/Health Example:

Relationship Example:

Skill Development Example:

The framework is domain-agnostic. What matters is:

Many people run parallel cycles — one for professional goals, one for personal goals — using the same framework for both. The structure ensures you’re applying the Law of the Vital Few across all areas of your life, not just work.

Accountability is built into the 12-Week Year system through multiple mechanisms. Here’s how to implement them:

1. Weekly Scoring (The Core Mechanism)

Every week, score yourself on whether you completed the planned actions for each goal.

This isn’t about perfection — it’s about honesty and measurement. If you planned 10 actions and completed 8, your score is 80%. Track this every week.

The weekly score creates a feedback loop. You can’t hide from the data. If you’re consistently scoring below 80%, you’re either planning poorly or not executing. Either way, you have information to act on.

2. Weekly Planning Sessions

Every week (ideally Sunday evening or Monday morning), conduct a planning session:

This ritual keeps goals front-of-center. Without it, urgency evaporates and goals drift into “someday” territory.

3. Accountability Partnerships

Find one person — a peer, coach, or colleague — who is also using the 12-Week Year. Meet weekly (or biweekly) to:

External accountability dramatically increases execution rates. It’s harder to let yourself down when someone else is watching.

4. Public Commitment (Optional)

Some people benefit from making their goals public — sharing them with a team, posting them in a community, or committing to them with stakeholders.

This works best for professional goals where transparency adds pressure. For personal goals, privacy is often more effective.

5. Consequence Design

Attach real consequences to non-execution. These can be:

The consequence should be meaningful enough to create motivation but not so severe that it creates anxiety.

The key insight:

Accountability isn’t about punishment — it’s about measurement and visibility. The moment you start tracking your weekly execution rate, behavior changes. You can’t bullshit yourself when the data is clear.

Most people don’t fail because they lack capability. They fail because they lack feedback. The 12-Week Year’s accountability mechanisms create tight feedback loops that keep you honest and focused.